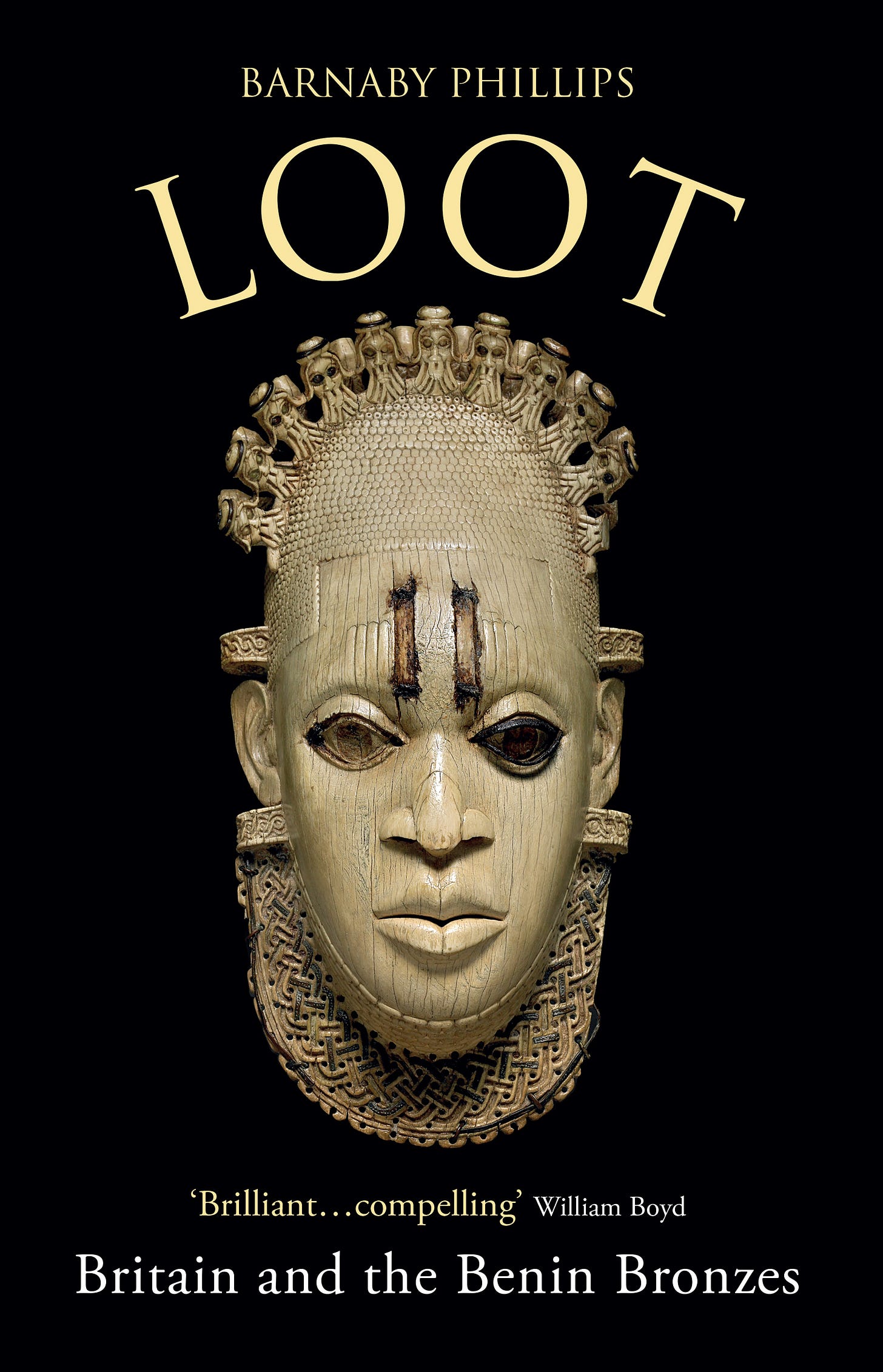

When the British invaded and looted Benin in 1897, they stole over 3,000 artefacts. The artistry was so exceptional that for more than a century, Europeans searched for alternative explanations for their origin. Some claimed the bronzes were made by aliens, others insisted they were the work of ancient Egyptians, and a few argued they were crafted by Europeans who had once visited and “taught” the Edo people. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that a scholarly consensus finally accepted the obvious truth: the Benin Bronzes were made by the Edo people themselves.

But that consensus hasn’t ended the debate. The reason is simple—hundreds of these bronzes remain in Europe. In recent years, activists have launched campaigns calling for their return.

That is the subject of this book.

When I picked it up, I was indifferent to the debate. I didn’t know much about the Benin Bronzes, and I wasn’t sure why their return really mattered. But Philip Barnaby cured that ignorance—and has turned me into a firm advocate for their repatriation. Barnaby is a lucid storyteller who doesn’t shy away from the complexity of the issue. In this book, he gives space to many voices: those in support of the bronzes’ return, those against it, and those caught somewhere in the middle. And he presents their arguments clearly.

One of the common arguments against the return of the bronzes is that they “won’t be properly managed” back home. I agree with the reason—but not the conclusion. You don’t return something because the owner can manage it well or not. You return it because it belongs to them.

I used to think it didn’t matter much. But now I realize it does—more than I imagined. The Benin Bronzes are not just artefacts. They are statements. Testimonies of the skill and vision of Edo ancestors—and of Nigeria’s long, sophisticated history. The presence of a great past often inspires the present to rise to its legacy. That’s why we need these bronzes back.

Will they be managed well? That’s a different question—and not one Europeans have any right to answer, or even ask. When Napoleon invaded the Papal States, he stole the Codex Vaticanus. After his defeat, it was returned. When Nazi Germany looted European nations, those artifacts were repatriated. International law is clear: the looting of cultural treasures is a crime against humanity. There is no legal or moral defense for keeping them.

Back to the Nigerian question of management: I hate to admit it, but the fear that the bronzes won’t be properly managed is not entirely unfounded. One of the most sobering moments in this book came when I read that, during Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Nigeria, then-President Yakubu Gowon walked into a museum and casually instructed the curator to hand him a major Benin Bronze to give the Queen as a gift. Just like that. It took the wisdom—and courage—of that curator to hide some of the artifacts to prevent further loss.

This happened at a time when global activists were already fighting hard for the return of the Bronzes. That kind of institutional carelessness—and leadership foolishness—is precisely why our national treasures remain vulnerable. Burglaries and thefts are surface problems. If you have leaders who think like Gowon, then there’s simply no way to build a culture of national preservation.

Contrast that with what I learned about the UK. In the UK, the government is legally barred from selling museum artifacts.

Politicians cannot interfere with or dispose of items held in national museums. That’s called institutional protection.

But this book is not just about the return of the Benin Bronzes. It’s the story of the Edo people—past and present. It begins with them, and it ends with them. It takes you through their first contact with Europeans, their early interactions, the tensions that followed, and the war that eventually led to the sack of Benin. It tracks how the bronzes were scattered around the world, how they ended up in various museums, and how some of them have found their way back.

Along the way, you meet a few quiet heroes. Kenneth Crosthwaite Murray, for instance—the man who laid the foundation for Nigeria’s museum system. Sadly, he didn’t live long enough to see his vision fully realized. And then there’s Mark Walker, a man who—tired of all the debate about how and when to return the bronzes—simply packed up the bronze he inherited and brought it back to Nigeria. No long talk. Just action.

Of course, the Obas feature heavily in this book. In many ways, this is also their story. It’s a shame that the museum project the current Oba began under Godwin Obaseki’s administration still isn’t finished. Nigeria, as usual, is already happening to the project.

Barnaby Phillips did an excellent job here. This is the kind of book you want to read when you’re curious about a subject—because he rewards that curiosity. If you’re interested in the Benin Bronzes, this is the book for you. If you love African or Nigerian history, this is the book for you. The storytelling is rich, and the nuance is breathtaking.

Pick it up.

You mean Gowon was offering bronze artifacts as souvenirs?

Are you sure the Nigerian leaders haven't traded their senses?

Thank you for this review.