This evening, I had a conversation with my good Zimbabwean friend, Tafadzwa Taffy Negonde Taffy Negonde. He asked if opportunities for scholarships to international universities are shared in Jenta. I told him no.

It’s not just that the opportunities aren’t there—it’s that the ambition for such a life barely exists. Growing up, I often heard parents say their child had "finished school," and by that, they meant he had written WAEC. For many parents in Jenta, O Level was the peak. How can one build a great life with such limited expectations?

Society expects little of you. It sets a low bar. The environment encourages mediocrity. If you grow up, get married in a church wedding, and spend the rest of your life in a two-room house, you are considered successful.

This is the "good life" in Jenta.

Four years ago, I volunteered to teach at a government secondary school. Corps members from the South West and South East were shocked by the students' performance—SSS1 students who still couldn’t write or do basic arithmetic. Worse still, many of them lacked interest in their academics. One day, I sat the corps members down and explained Jenta to them. After that, they never complained again. Some resolved to do their best, but most simply lowered their standards to match the low bar they found. And so, the cycle continues.

One of them asked me: Why volunteer to teach when you already know what the situation is? Why waste your time when it seems almost hopeless?

I told him it wasn’t hopeless. But if you don’t fully understand the situation, you can’t fight it. You could be teaching one thing in class while the kids hear something entirely different on the streets. You could be explaining math to a child who is more worried about his father’s health. You could be preaching the value of hard work to a student who has only seen hardworking people struggle without reward.

During that time, I visited many students in their homes. I connected with them and their parents. I made them understand that I expected something of their lives—not because I wanted to feel good about myself, but because they were human beings, with abilities, with potential. A child in Jenta is no less capable than a child in California.

I wish I could tell you that many lives changed. They didn’t. I left after a few months, as we all do.

But something bright came out of it—some of those students became friends. We stayed in touch. We still talk. When their parents faced challenges, they called me to speak to them. And in every case, the students listened. It even became a family mantra to say: "I will tell Uncle Lengdung you are doing this or that."

Four of them went to university.

For Jenta, you don’t need to change everyone. Just a few.

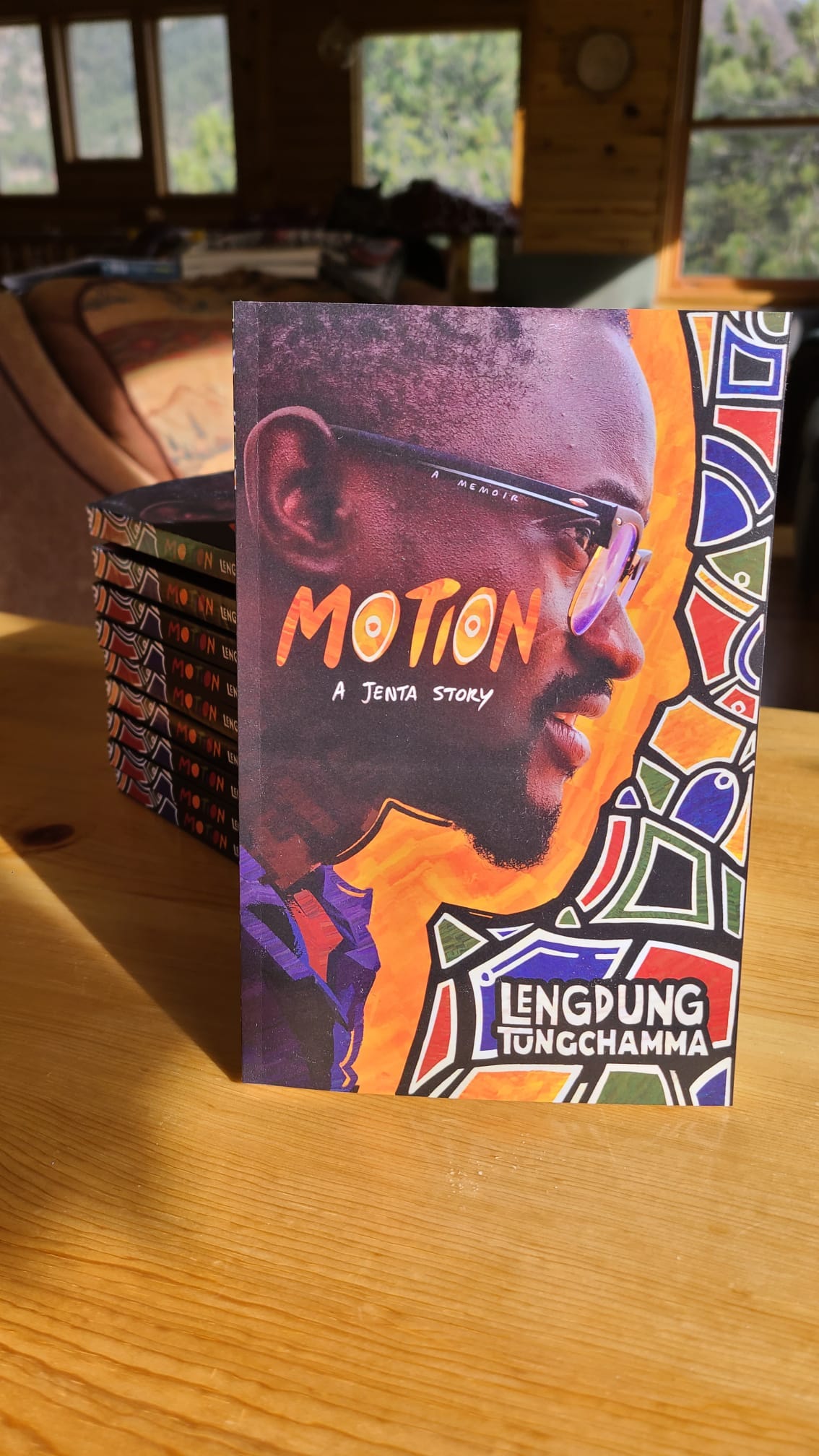

That is what Jenta Reads has always been about.

There is only one way to break this chain. Those who have been fortunate enough to escape must go back and do something.

I know—we were lucky to escape. Too lucky. There was nothing special about us. Nothing.

The least we can do is break the cycle.

I hope this book helps in understanding that cycle—and in breaking it.

First, how did we escape?

This is the highlight of this post for me🥹…

“I visited many students in their homes. I connected with them and their parents. I made them understand that I expected something of their lives—not because I wanted to feel good about myself, but because they were human beings, with abilities, with potential.”

I’m volunteering in a community where their educated children stop at primary 6. The 3 teachers in the community are no better than a nursery 2 kid in the city. Reading this has inspired me on ways to connect more with my pupils & not give up. Thank you god sharing.

This is deep: "Those who have been fortunate enough to escape must go back and do something."

Many people aren't interested in giving back. Thank you for doing so, Lengdung! I cannot imagine what it felt like to live in a place were possibilities were non-existent.